“Well, I guess no one’s going to call. OK, let’s get this over with.”

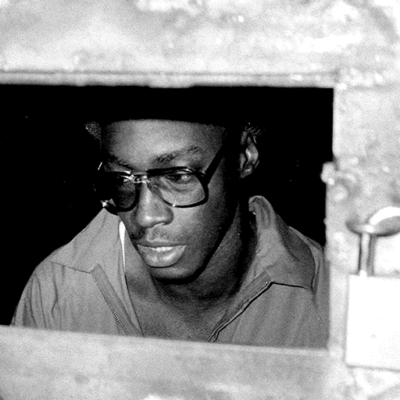

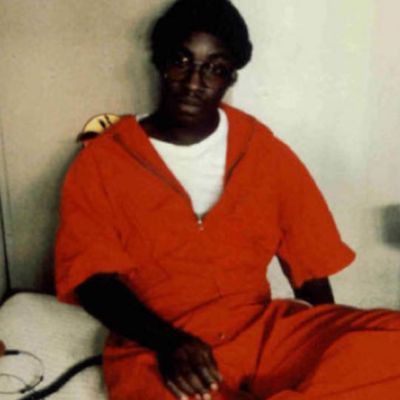

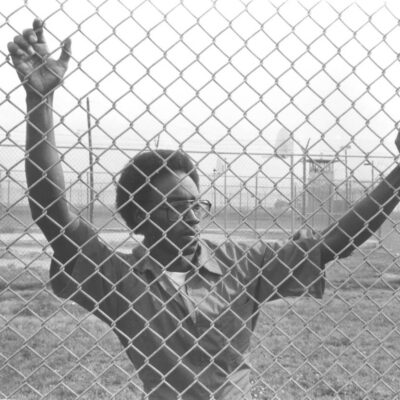

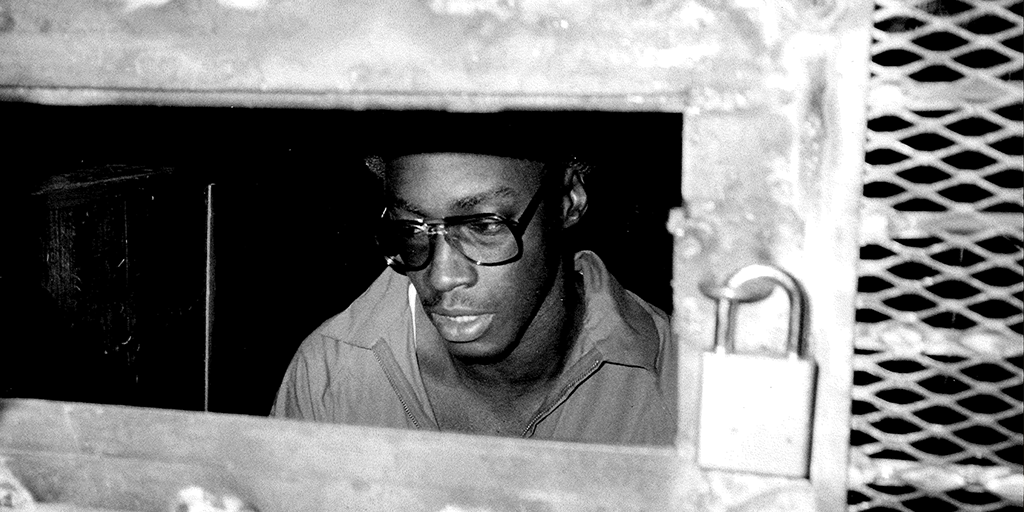

Edward Earl Johnson

This is what Edward Earl Johnson said on May 21, 1987.

He was already strapped into the chair in the Execution Chamber, waiting for the State of Mississippi to poison him with cyanide gas. Edward was just shy of 27 years old.

Edward was born in Walnut Grove, a small village a few miles south west of Philadelphia, Mississippi – best known for the notorious murder of the three young civil rights workers (Michael Schwerner, James Chaney & Andrew Goodman), later the subject of the film Mississippi Burning. The three young men, guilty only of a voter registration drive, were killed as midnight turned into June 22, 1964 – Edward’s fourth birthday.

Unfortunately, when Edward faced prosecution less than 15 years later, local race relations had not changed very much.

Source: Paul Hamann, 14 Days in May.

His mother left Walnut Grove to seek a better life as an auxiliary police officer in New York. Her own mother, Jessie Mae Lewis, raised Edward. Jessie Mae was firm but fair, and brought him up to respect authority, a quiet spoken young man who enjoyed playing chess.

Edward was convicted of murdering Marshall J. T. Trest and assaulting an elderly woman named Sallie Franklin. There could be no doubt that Trest – who had arrived to investigate Franklin’s assault – was an innocent victim, but there was plenty that was very dubious about the case from the start: Jessie Mae worked for Sallie, who knew Edward well.

Source: Paul Hamann, 14 Days in May.

On the morning after the murder, the white sheriff had paraded many of the black male youth of Leake County in front of her. She was certain that Edward had nothing to do with it.

Later, at trial, she was equally emphatic that Edward was the one. But such inconsistencies didn’t matter in Leake County in the 1970s: the word of a white woman could never be outranked by a young black man.

Edward spent eight years on death row. He was innocent.

The main evidence used to convict him was a ‘confession’ that he did not write.

The police asked Edward to take a polygraph. He agreed. Two white police officers drove him to Jackson 40 miles away. But they stopped and pulled to the side of the road before getting there. There, they told Edward that they could shoot him. They would just have to say Edward had tried to run away. That is how his ‘confession’ was extracted.

Source: Paul Hamann, 14 Days in May.

They went back to Walnut Grove and allegedly recorded his ‘confession’. The recording never saw the light of day. Only the written version was used at trial.

At Edward’s funeral, his friend Big Mary revealed that he couldn’t have committed the crime because he had been with her at the time. When Clive Stafford Smith asked why she didn’t tell anyone that, Mary said: “I did. I went to the po-lice and they told me to go home and mind my own business.”

Clive was Edward’s lawyer in those last, desperate three weeks running up to his execution, though he was the same age as his client and woefully inexperienced. His efforts to save Edward’s life were captured in Paul Hamann’s BBC documentary 14 Days in May.

This documentary had a huge and lasting impact. It lead Clive and Paul to found Reprieve, it inspired a generation of young people to fight against the death penalty, and it has frequently been named as one of the must-watch documentaries by film makers like Louis Theroux.