This article was first published in TLS on June 18, 2020. The original version is available here. It is reproduced with permission from TLS. Explore our website to find out more about Edward Earl Johnson.

This week, on June 22, Edward Earl Johnson would have been sixty. Instead, he didn’t quite make it to twenty-seven.

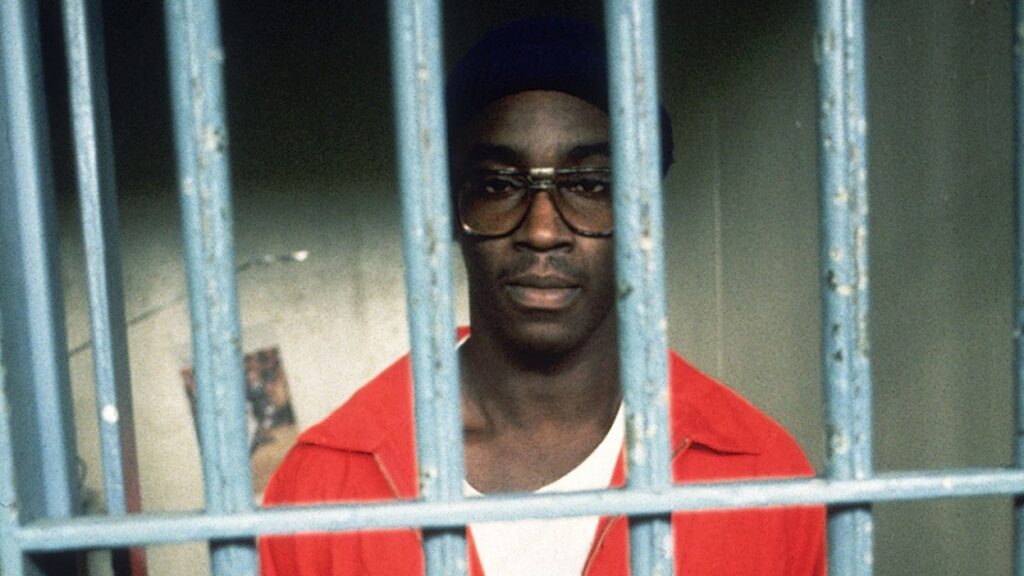

Just after midnight on May 21, 1987, I watched as Edward slowly choked to death, gulping in cyanide gas, a means directly descended from the Zyklon B used on an industrial scale by the Nazis. A few minutes earlier, I had walked with Edward into the awful, oval Mississippi gas chamber, and hugged him before the guards strapped him tightly down to the chair. I then waited ten minutes – it seemed hours, and it seemed seconds – in a witness chair, behind Edward, only able to see the back of his head. (This is a key part of execution protocol: they don’t want you to see the agony on a prisoner’s face as he or she dies.) Edward finally spoke, mostly to himself. “Well, I guess no one’s going to call. OK, let’s get this over with.”

I hold myself responsible for Edward’s death. I’ve had plenty of opportunities to think about it. Paul Hamann filmed the two weeks running up to this catastrophic finale for his film, Fourteen Days in May (1987), so I have the dubious luxury of being able to replay the grandest failure of my life whenever I want.

It was long after midnight and I had come from breaking the news to Edward’s family that he was dead. Now it was my chance to vent to the media. “What was I meant to tell them?” I demanded of the journalists assembled before me, in their pecking order, from the TV crews with their tripods, down to the newspaper journalists sprawled on the cheap nylon carpet. “It’s a sick world. It’s a sick world.”

Then I almost killed myself driving the 128 miles to Jackson, alternately weeping and dozing at the wheel. I had to go on to Atlanta the next morning, but it was less than a week before I was back for Edward’s funeral. It was a traumatic affair for everyone, all the more so for me when I talked to his friend Big Mary. She told me that Edward could not have done the crime, as she had been with him at the time.

“Why didn’t you tell someone that?” I blurted out.

“I did”, she replied. “I went to the po-lice and they told me to go home and mind my own business.”

Big Mary had told this to the white Leake County law enforcement officers, who were then investigating the murder of a white town marshal and the alleged assault of a white woman – crimes they supposed had been committed by a black man. I should have been the one who tracked her down well before Edward’s execution. In truth, I only went once to his home town of Walnut Grove in the limited time we had, to pay my respects to his lovely grandmother, Jessie Mae Lewis. I met Big Mary for the first time at the funeral.

I was also twenty-seven when I took on Edward’s case in an effort to fend off an execution then just days away. I was in the full arrogance of youth, and in my very brief legal career had yet to see a client executed. I did not expect to lose. I had been to a prestigious law school and was sure that some clever legal wheeze would see him safe. I was not wholly without imagination – in the limited time we had, I got a personal intervention from Pope John Paul II calling on the Catholic governor, Bill Allain – a Democrat – to spare Edward’s life (“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy”). Yet that was wasted energy. I should have known that a pending re-election would be far more persuasive to Allain than the threat of eternal damnation.

As I look back now, after more years than Edward was allowed to live, I see it clearly: if I had known then what I know now, he would be alive today. His mother was an auxiliary police officer in New York, so perhaps, after his stay of execution and subsequent exoneration, he would have chosen to head north, away from all the Deep South prejudice. Perhaps he would have married. I remember the way his niece sat on his knee during the family’s final visit. I can imagine him with the children, maybe now grandchildren, listening to his soft Southern lilt.

Edward had been convicted of the murder of Marshall J. T. Trest and the sexual assault of an elderly woman, Sallie Franklin. There could be no doubt that Trest – who had arrived to investigate Franklin’s assault – was an innocent victim, but there was plenty that was very dubious about the case from the start: Jessie Mae worked for Sallie, who knew Edward well. On the morning after the murder, the white sheriff had paraded what seemed like most of the black male youth of Leake County in front of her. She was certain that Edward had nothing to do with it. Later, at trial, she was equally emphatic that Edward was the one. Such inconsistencies hardly mattered in Leake County in the 1970s: in matters of sexual assault, the word of a white woman could never be outranked by a young black man.

Jessie Mae managed to rustle up the money to hire R. Jess Brown. When I met him, Brown explained to me that he used to change race when he crossed the Louisiana–Mississippi border. Louisiana used to define being “black” as having one-eighth African heritage, while Mississippi opted for one-sixteenth. Brown had light skin and was only deemed black in Mississippi. Early in his career, he had courageously taken a stand when he represented Mack Charles Parker, accused of raping a white woman in 1959. Brown challenged the all-white jury panel. Rather than deal with legal challenges to their supremacy, the local racists donned their hoods, seized Parker from the jail and threw him into the Pearl River, weighted down with chains.

Twenty years on, when Edward was arrested, not all that much had changed. Brown was threatened when he came into Leake County to represent another black man who was presumed guilty. Perhaps understandably, he did little by way of factual investigation into whether Edward actually committed the crime. If he had, Edward might have lived – but, then, Brown might not have.

As a privileged white male, I did not have the same excuse for inaction. I should have found Big Mary, and gone where she led me. My problem was that I was simply ignorant – too ignorant to be trusted with a life.

Beggars can’t be choosers, even when they face death: Edward had to put his trust in me, along with two of my friends (who will not share my blame here). After all, like everyone I have ever represented on death row, he was indigent – capital punishment is when those without the capital get the punishment. Mississippi did not provide Edward with a legal aid lawyer. Two years later the Supreme Court would confirm, in Murray vs. Giarratano (1989), that no matter who might find himself on death row – young, innocent, intellectually disabled or illiterate – they had no right to counsel. It was sufficient, the court held, that there be a prison law library where the condemned could read about cases, and “inmate counsel” (other prisoners) who could “advise” him.

This was ridiculous – and remains the case, with arbitrary exceptions – and it meant that Edward had to accept my help: the help of a volunteer do-gooder. I learnt a great deal from his case, but it came at his expense. I know now that there were any number of ways in which I could have stopped his execution. First, what he needed was a vigorous factual investigation to prove his innocence, rather than a series of legal theories I’d digested from a dusty law library. I went back to Walnut Grove with Paul in 1988 to make a follow-up film, The Journey. We interviewed Big Mary and other alibi witnesses; we also tracked down the person who probably shot the town marshal. Various people identified the man, and it wasn’t hard to find him. I went in with a wire to talk to him in a seedy motel in Alabama. When I eventually asked him whether he killed Trest, all he could offer was: “I don’t remember”.

The second thing I could have done for Edward was buy him more time, with any number of legal stratagems. I could have challenged the gruesome way in which they planned to kill him. I figured this out eventually. On January 27, 1995 – the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz – with a Holocaust survivor as co-plaintiff, we sued to eliminate the gas chamber from Mississippi. Oddly, Governor Allain, who had in any case lost his re-election bid a few months after the execution and was now back in private legal practice, was representing the State of Mississippi. When I stopped by his office in Jackson to discuss the suit, he wanted only to talk about Edward. A white woman, he said, had come to him with proof that my client had been innocent, and he was racked with guilt. We did work out an agreement to end the gas chamber, but that was small solace for Edward’s family.

Instead of bowing to an absurd system, I might also have objected to the risible lack of resources provided to Edward. Again, that came to me much too late. In 1999, I won a stay for Willie Russell, with forty minutes to go, based on his lack of legal aid. He was an intellectually disabled African American facing execution without so much as a pencil to defend himself. To illustrate the folly of the system, we demanded that Willie be granted a weekend furlough from death row to allow him to interview witnesses if he were not allowed a lawyer. We then scheduled the depositions of the Mississippi Supreme Court justices with notice that we planned to ask them on video to describe how Willie was meant to defend himself. At this point the Court miraculously found that the state should give him a lawyer, albeit still woefully underfunded. Russell was later taken off death and subsequently returned to it; he died (in 2017) before we could finally resolve his case.

When Paul’s documentary was broadcast on BBC1 later in 1987, there were more complaints about the gassing of a black bunny rabbit (a procedure to ensure the operationality of the chamber) than there were for Edward – yet the film did make an impression on many. It spawned two organizations – Lifelines and Human Writes – whose members became pen pals to those on death row. And a slew of young people volunteered to join the battle in the Deep South, inspired by Edward. When it comes to the death penalty, however, it is at best two steps forward, and one back. The US execution rate has slowed to around twenty per year, but there are still some 2,600 people waiting to die. It would take 130 years to clear death row at this rate, and something will have to give. With the cyanide gas chamber gone, we next proved how grotesque lethal injection can be. In response Mississippi has authorized going back to the chamber and experimenting with nitrogen gas.

When it comes to the innocent, our record seems to be getting worse. Two of the six executions in the US so far this year have involved strong claims of innocence. Alabama executed the African American Nate Woods in March for his involvement in the murder of three white police officers, even though nobody pretended he shot anyone, and his accomplice Kerry Spencer made an extraordinary plea from his own death row cell: “Nathaniel Woods is 100 per cent innocent, I know that to be a fact because I’m the person that shot and killed all three”. Last month Missouri executed Walter Barton for the fatal stabbing of an eighty-one-year-old woman in 1991, in as weak a prosecution case as one can imagine: no eyewitnesses, no meaningful physical evidence, and DNA under the victim’s fingernails indicating that someone else was involved in her final struggle. After failing to secure a valid conviction in four trials, in the fifth the state used three jailhouse snitches who, in exchange for favourable treatment, “recalled” tales of Barton boasting about the murder.

I try not to watch Fourteen Days any more. I find it hard to suppress my own wrath when I think of the softly spoken Edward in his prison cell, watching his battered television, as callers to the news programme lined up to howl for his execution. In the end, though, they were guilty only of spouting venom. I am the one who actually let him down.

Clive Stafford Smith is a US lawyer and founder of the London legal action charity Reprieve. He specializes in civil rights and working against the death penalty