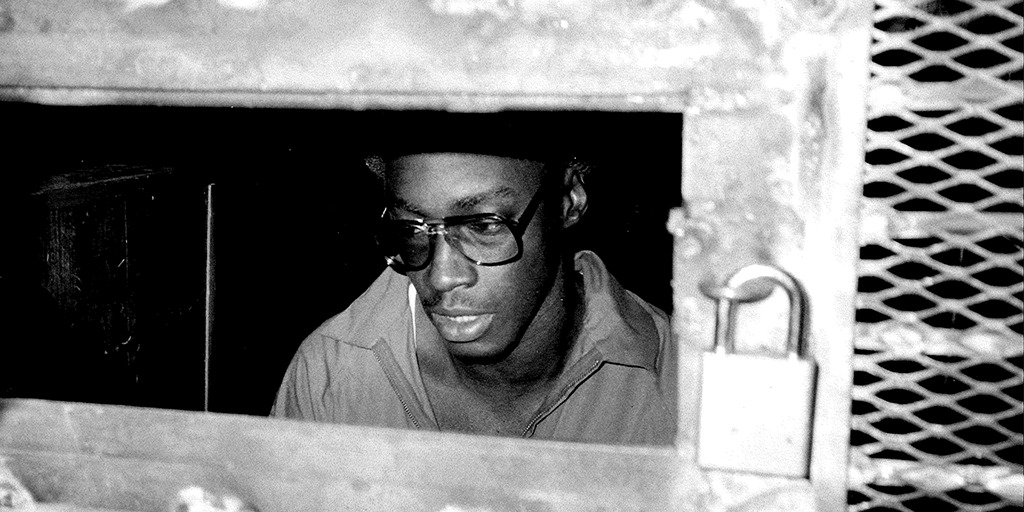

31 years ago, on May 20, 1987, just before midnight, I was sitting in the witness area of the Mississippi Gas Chamber watching someone die in front of me. His name was Edward Earl Johnson.

I am both sad and glad that Edward’s final two weeks, right up to his agonising death, were recorded in Paul Hamann’s extraordinary BBC documentary Fourteen Days in May. Sad, because from time to time I find myself forced to relive that horror, when I watch the film at some public event; glad, because at least Edward’s senseless death has had positive repercussions – the film inspiring many to take up the battle for people in his precarious predicament.

Yet it irks me beyond measure that people who should know better use their position of power to prognosticate that the justice system never executes the innocent. For example, in a case called Kansas v. March, in 2006, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia loudly proclaimed that there is not “a single case — not one — in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit.”

Of course, in a way it is not surprising that Justice Scalia made his foolish statement. After all, he did not think his job included protecting an innocent person from the Chamber. In Herrera v. Collins he opined that “there is no basis … for finding in the Constitution a right to demand judicial consideration of newly discovered evidence of innocence brought forward after conviction.” What he meant in plain English was that the Supreme Court should not stop an execution merely because someone was innocent. This remains the law today, which makes it particularly difficult to prove that a prisoner did not commit the crime once the jurors have made their original mistake.

When we do try, the prosecution invariably turns to Justice Scalia’s words and responds as they did last week in the case of Kris Maharaj, the British man sentenced to death for a crime he did not commit in Miami in 1986. “Claims of actual innocence based on newly discovered evidence,” the assistant attorney general assured the federal court, “have never been held to state a ground for federal habeas relief.”

Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.

On February 13, 2016, Justice Scalia died, leaving this as his sorry legacy. He cannot change his foolish opinions now that he is dead; and neither can an executed prisoner clear his name post mortem because his innocence has become “moot” in the quaint terminology of the court.

The labour activist Mother Jones admonished us to “pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.” For three decades, I have followed her advice, but I wonder if it is not time to change. I am thinking we need to fight like hell for some of the dead. They have no voice, and they never had one.

Since the U.S. resumed executions in 1977, we have exonerated 162 people who were sentenced to death – fully one for every nine people executed. At each of 162 trials, twelve jurors were convinced beyond a reasonable doubt of their decision – so sure that they imposed death. Yet we are meant to believe that somehow they got it right every time someone got through to the Chamber? This is no more than an executioner’s wishful thinking.

If I knew then what I know now, Edward would be alive today

Edward was innocent and I watched him choke to death. I encountered a young African American woman at the time of Edward’s funeral who said she had been with him at the time of the murder of Walnut Grove Town Marshall J.T. Trest. She had, she said, been to the (white) police to tell them he could not have done it, but they told her to mind her own business. I later spoke with Governor Bill Allain, the guilt-ridden Catholic who denied Edward clemency. He told him how a local white woman had come to him to tell him who actually committed the crime, and why. I have some guilt myself, since I was very young and inexperienced in 1987, and if I knew then what I know now, Edward would be alive today no matter what everyone else did or did not do.

However, it is time for us to prove our point – beyond my personal experience. It is time to prove, for example, that in 2004 Cameron Todd Willingham was executed for the tragic deaths of his children in a fire that was wrongly determined by an expert, now debunked, to be arson. Can you imagine the primordial horror when a parent finds himself unable to save his three kids from the fire – two-year-old Amber and one-year-old twins Karmon and Kameron. Yet this was followed by a sanctimonious prosecutor painting falsely him as a premeditated killer, sending him for 13 years on death row before attending his execution.

And so I could go on through many cases. Meanwhile, as I take a moment today to reflect on how I failed Edward Johnson, I feel I have a duty to nail the coffin firmly shut on his conviction: his name, and the names of many others, need finally to be cleared beyond all doubt.